Stop Blaming Spotify for the Wrong Thing

The CEO’s portfolio is messy, but it’s distracting us from a product strategy that’s turning music into AI filler – a gamble that might backfire.

A billboard from Spotify’s 2019 out-of-home campaign, Music for Every Mood

“Anyone can play guitar

And they won’t be a nothing anymore.”

Radiohead, 1993

When I was an underpaid intern in Rome, around 2010, I fell in love with a blog that bottled the energy of L.A.’s indie scene. Buzzbands.la felt like oxygen in a pre-streaming world: free MP3s from hungry bands, handpicked by people who cared. It was a window onto the West Coast, a way to hear what was next, earlier than everyone else.

The thrill was real, but so was the pattern. Playlist after playlist, I stacked CDs (!) of songs that were… almost OK. Pleasant, familiar, polished – yet somehow lifeless. Over time, I developed a guilty pleasure: I began to autopsy the misses. Why did a track feel catchy at first, then instantly forgettable? Weak chorus? Copy-paste melodies? A flat vocal interpretation?

No beauty is more tragic than the one that nearly is.

Fifteen years have passed. It’s no surprise that, despite the fire and ambition poured into those singles, most of those bands faded without leaving a trace. Their members have likely moved on – chasing new dreams, living quieter lives. Maybe, somewhere, they’re telling their kids stories about the time they almost made it in L.A.

Fifteen years later, their kids have a platform that delivers “almost OK” music at infinite scale. It’s called Spotify.

When Spotify launched in 2008, this was its homepage

Was I too hard on Spotify? Not long ago, writing a post like this would have put me on the wrong side of history – a luddite in skinny jeans, signaling resistance for the sake of aesthetics. But the vibe has shifted. These days, calling out Spotify doesn’t make you anti-tech – it makes you a consumer with ethical concerns.

Did we finally wake up to Spotify’s broken economics – the payout model that leaves thousands of musicians working for almost nothing?

Not even close. Now, Spotify is under fire for hosting recruiting ads from ICE, and for complicity Israel’s genocide against Palestinians in Gaza. The backlash peaked when CEO Daniel Ek doubled down on his 2021 investment in Helsing – a German defense tech startup building AI-powered weapons: combat drones, surveillance tools, the works. (To be fair: Helsing is deeply involved in the Russia–Ukraine war, not Gaza.)

If you start looking for a more ethical streaming option, prepare for whiplash: there are red flags in every direction you turn. Deezer is owned by Russian oligarch Len Blavatnik, philantropist yet quite controversial figure; YouTube Music is owned by Google, which has a few antitrust and tax gymnastics issues, and provides cloud services to the Israeli Ministry of Defense; Apple has some ethical gaps, too (labor abuses in China, greenwashing, antitrust, to name few); Amazon Music is not owned by the most ethical company in the world; Tidal is controlled by heavy backers of an environmentally-disastrous technology called bitcoin.

The longer the list goes, the more it feels like I’m steering toward that familiar, whataboutist conclusion: all companies are evil, stop asking the wrong questions, and just keep your Spotify subscription.

Trust me, I’m not. I’ve got 4,000 more words to prove it.

I’m not here to dictate your moral compass. How you spend your money shapes the world, and conscious consumer choices are always good news. I only worry about where and how we hold this company accountable.

Most criticisms hinge on indirect ties – sometimes as slippery as correlation. Take boycotting Spotify over Gaza, even though its CEO’s investments are linked to Ukraine instead. Don’t get me wrong: there are no good wars, and indirect links do play a role. But it’s surprising how much they overshadow the direct choices Spotify makes every day about its product and ecosystem.

The real story isn’t about ethics by association. It’s about incentives embedded directly into Spotify’s product. Those daily, deliberate design choices shape what music becomes and how we listen.

We should be asking different questions: what kind of culture do Spotify’s incentives create? And what future of music are we allowing to take shape?

I told you – I have 4,000 more words ready. Because if we don’t understand the root cause, we’ll keep blaming Spotify for the wrong reason.

And yes, I’m sorry: at some point this becomes another article about AI.

1. Why Spotify’s Metrics Broke Music

We Shape Our Tools, Then They Shape Our Culture

On platforms and sometimes in life, you get what you reward. Spotify’s north star is streams – the music industry’s version of impressions, one of the most overrated metrics of the decade. A stream triggers after just 30 seconds. It does not matter if a listener starts streaming from beginning, middle or end. As long as a song is streamed for at least 30 seconds, it counts as a play. It doesn’t care whether you chose the song, paid attention, or even liked it.

That’s the flaw with impressions: the memorable ones count the same as the meaningless ones. It’s a metric built for volume, not value. And when stream count becomes your north star, you inevitably design for distracted use – because distracted users tend to stream more. The most rewarding user persona is one that lets music run in the background while working, commuting, or sleeping.

The paradox was exposed by the band Vulfpeck with a stunt back in 2014: the four horsemen of groove released Sleepify – ten ~30-second tracks of silence – and asked fans to loop it while they slept to fund a free tour. This loophole exploitation earned $20,000 before Spotify pulled the album. You get what you reward: optimize for streams, get behavior that maximizes streams – attention optional.

Vulpeck were just a bit ahead of their time: sleep playlists are now huge at Spotify. According to Rolling Stone, at its peak, the soothing songs of Sleep Fruits Music Well, generated around 10M daily streams – at the time, that was more than Lady Gaga.

So who loses? Listeners who care about music as an experience. Artists reduced to content suppliers in an endless scroll. Optimize for volume and you get products – and eventually, culture – built for background noise.

The tragedy of modern music isn’t that people are making worse art. It’s that the system rewards the art that asks the least of us.

But it doesn’t have to be this way.

Is There Any Alternative to This?

Is there an alternative to Spotify’s ad-supported freemium model, that rely on metrics optimized for volume and virality? In other terms: is Spotify the bad guy, or just the biggest one in the room?

Tidal communicates a different set of metrics: their growth narrative is more qualitative, emphasizing product differentiation (e.g., sound quality, artist equity) rather than scale. It reinforce the artist-first narrative of their model, which revolves around a premium niche (as opposed to the mass market, ad supported model of Spotify).

Idagio focuses on classical music listeners, and its metrics reflect a curated, expert-driven experience: they track searches by movement, conductor, interpretation (unique to classical music); they decide weekly what’s musically significant to promote; they leverage tools like Braze and Looker not just for volume but for qualitative insights into musical interest.

The uncompromising users have now a soft spot for Qobuz, the independently-owned high-quality streaming platform. Qobuz tracks streaming and download volumes in 24-bit Hi-Res formats, which are central to its value proposition – "a digital record store in a world of supermarkets." Yes, downloads, you read it well: Qobuz complements streaming revenues with Hi-Res downloads, “to support musics outside of just Top 40 hits”. We’re at the extreme opposite of Spotify – it’s no place for playlist skimmers.

But these are companies that operates on a different scale. Spotify is a publicly traded company that holds over 30% of the global music streaming market. The closest competitor, Apple Music, hasn’t even half of its market size. You have to multiply Tidal by 140 times to make it the size of the king of the forest. If you consider Idao, the classical music streaming platform, you have to multiply for 390. Qobuz, well: it’s hard to point as a reference a platform that has 1/3480 the monthly active users of Spotify.

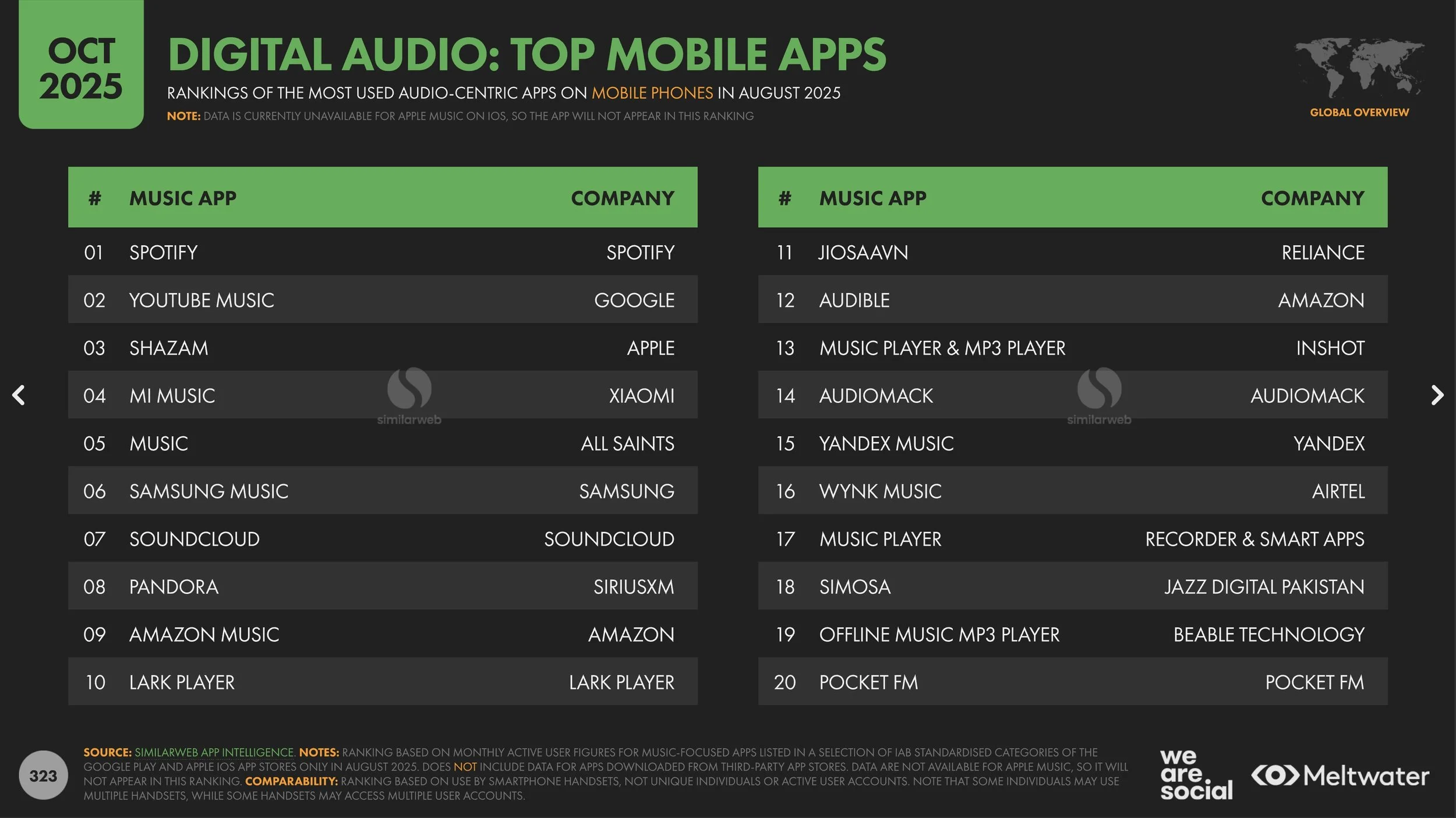

The most used audio-centric apps on mobile phone worldwide. Data from Digital 2026 Global Overview Report. Read more here

Also, these alternatives have also still to prove that they find a viable business model. Tidal is stable but struggling in profitability (one year ago, their main investor, Block CEO Jack Dorsey, stated that they needed to "part ways with a number of folks and start operating like a startup again"). Idagio is in restructuring, Qobuz is not profitable. You can’t use them as a reference and being taken seriously.

But that doesn’t mean that there is no way to balance the metrics mix of a mass player. We’ll get back later on this. For the moment, let’s just name a few fixes, just to show that there are alternatives, if we want to find them.

For instance, if Spotify wanted to reward meaning over throughput, it would elevate metrics that correlate with attention and emotional investment:

Intentional Plays per User: user-initiated starts, not autoplay.

Repeat Listening Rate: do you come back because it moved you?

Saves & Adds: put it in your library or on your playlist?

Discovery Depth: did you explore beyond the first recommendation?

These aren’t cute dashboard ornaments – they’re a design brief for a software that has an unmatched cultural footprint. Every correction in Spotify’s trajectory reshapes the product and, at its scale, the culture.

Look, I’m not that naïve. I know Spotify isn’t run by amateurs – it’s a public company with hundreds of designers and thousands of engineers. Their design system, Encore, is a benchmark for balancing autonomy with consistency. They publish solid research on algorithmic bias and know how to deploy changes at massive scale. If you’re curious, check their design blog, engineering blog, or even, well, obviously, their podcast NerdOut@Spotify.

I know that enterprise product management looks simple from the outside, but inside it’s brutal. Every strategic move requires buy-in across layers of stakeholders and shareholders. That complexity matters – and it explains why even smart teams can end up optimizing for the wrong things.

To their credit, Spotify doesn’t just chase streams blindly. They use a multi-metric approach to guide decisions:

Success Metrics: Engagement, retention.

Guardrail Metrics: Stability, crash rates, latency.

Deterioration Metrics: Detect negative impacts.

Quality Metrics: Broader indicators of user experience.

These feed into a risk-aware decision framework embedded in their experimentation platform, Confidence. They even analyze quantiles to see how changes affect different user segments – optimizing for inclusive impact, not just averages.

So yes, Spotify knows what it’s doing. But here’s the paradox: with all this talent and rigor, why does the general feeling about Spotify keep getting worse?

Experience taught me this: when you’re too deep in the effort, you need outsiders – people free from company bias – to make things look easy. It’s a privileged perspective, and I intend to keep it.

Because Spotify now faces two big issues – and no clever metric mix will fix them.

2. The AI Flood and What It Means for Creativity

From Art to Engagement

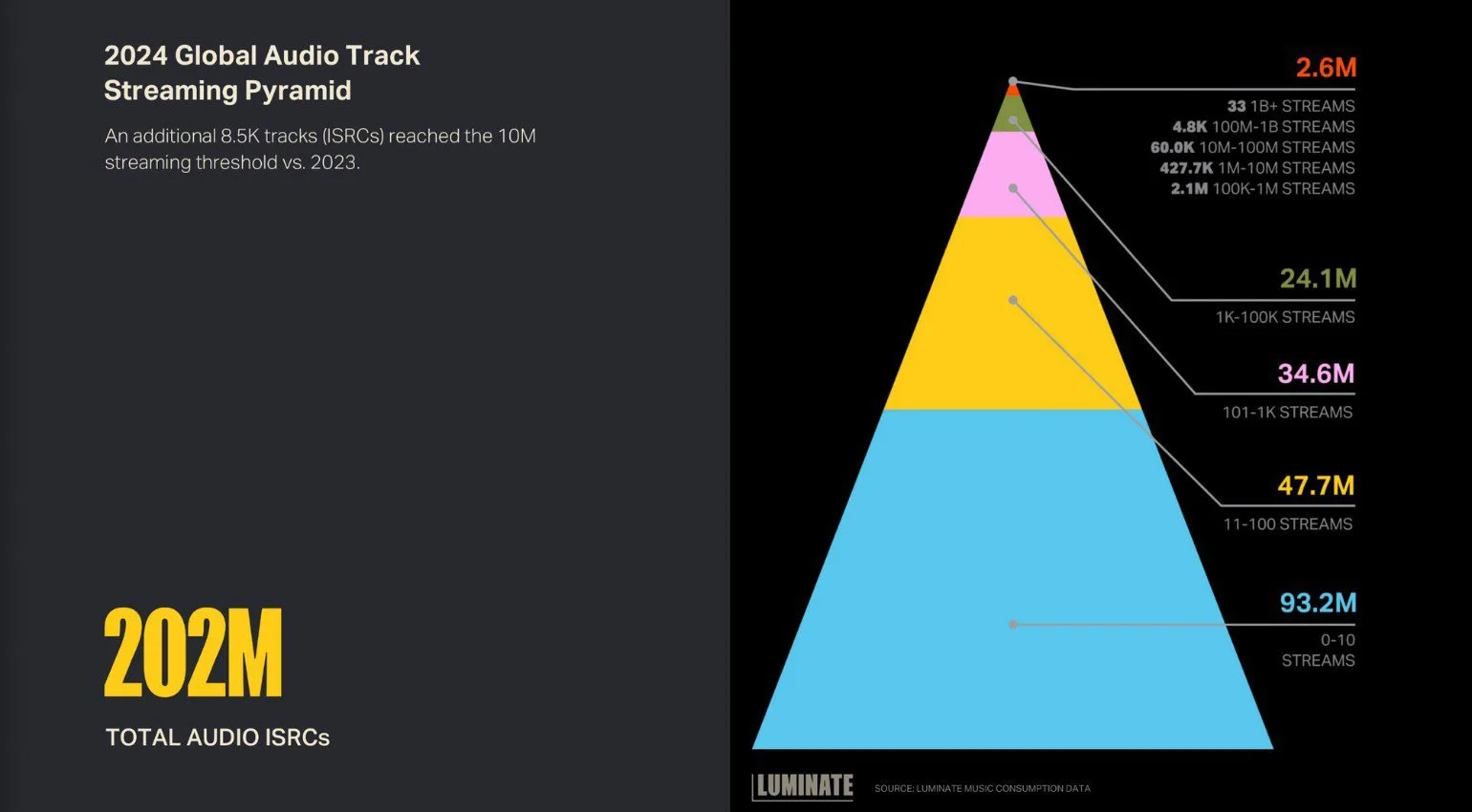

The damage multiplies when supply explodes. Low barriers to distribution (and now low barriers to creation) led to a flood of new music ready to feed streaming platforms. According to Luminate, on average, around 99,000 new tracks were uploaded per day in 2024, a slight decrease from 103,500 uploads per day the year before. At the end of 2024, a total of 202 million individual tracks were available on audio streaming services.

As music economist Will Page put it, “More music is being released today (in a single day) than was released in the calendar year of 1989.”. And when the noise floor rises, genuine signal gets buried. We’ve gone from generations where scarcity determined a narrow and deep focus (most of us still loop teenage favorites) to the next generation where an almost infinite abundance results in a wide but potentially shallow focus.

This oversupply of content made the abundance of choice overwhelming. The democratization of distribution should have been a renaissance. Instead, it gave us a platform that can surface millions of tracks while ensuring almost none persist in memory.

There are 50 million song with no listeners at all. Around 87 per cent of all tracks on streaming platforms receive fewer than 1,000 plays per year. Source: Luminate

When platforms drown in content, they lean on algorithms to keep people tuned in. Early on, the goal was simple: quantity over quality – helping you find the best so you wouldn’t get lost. Now, it’s almost all about one thing: user retention.

It’s not the playbook that everyone is using: YouTube Music leans on recommendation, but still supports user-initiated actions as a core part of the experience.

Spotify, by contrast, has moved toward autopilot features (AI DJs, Smart Shuffle) that steer listeners into passive consumption. It mirrors Netflix’s “comfort food” strategy: when choice overwhelms, make the platform decide. It’s a transition that smooths all the sharp edges: you turn to a safer, more uniform product, to rewards the casual listeners (the same group we’ve said drives the biggest profits).

Netflix’s “Play Something” is the archetype of these features: if choice is overwhelming, press the button and we’ll pick for you – comfort food for attention. Music streaming platforms are increasingly the same: no country for outliers.

“On the platform, you didn’t need to make a hit to succeed. You just needed enough of everything to attract anyone.”

At Netflix, this transition was deliberate: as this long analysis by Will Tavlin puts it, if the streamers’ “executives learned anything from indie film it was this: on the platform, you didn’t need to make a hit to succeed. You didn’t even need your film to be remembered. You just needed enough of everything to attract anyone.”

Spotify’s shift was different. It started as a market condition: there is simply too much music being released. The streamer built the stage, and a mix of low barriers plus poor product choices made it a stage for background content.

It’s a very tricky situation, but it is always darkest before it gets… pitch black. Enter Suno.

Everyone is a Musician Now

Before, abundance came from low barriers. Now, AI has taken creation to zero cost, unleashing a wave of user generated content that is flooding music platforms. We’ve seen this pattern before: Instagram turned everyone into photographers, TikTok into videographers; now, thanks to AI, music is next.

“I have no musical talent at all, I can’t sing, I can’t play instruments, and I have no musical background at all””

Skills are becoming optional: you don’t need to read sheet music when you can compose in English.

It’s easy to mock the new generation of AI music creators, some of which are proudly illiterates: “I have no musical talent at all, I can’t sing, I can’t play instruments, and I have no musical background at all”, said Oliver McCann, a British AI music creator who releases tracks as imoliver.

There’s an heated debate about their art, but we’ll skip it: no offence, but they’re not here to stay. Machines will replace them soon. Imagine an on-demand experience that mimics your favorite artist, in any style you want (“Here’s Taylor Swift but played by Slayer – just as you requested.”)

According to MIDiA’s research, “AI’s biggest impact will be its opening up of the consumerization of music. The days of audience, creation, rights and distribution being discreet sectors are numbered”. Read more here.

Actually, calling them remixes is not that accurate. We’ve moved past sampling, that was the way we used to do this in the last decades: you sliced old tracks to build new ones.

The new trend has a name you might not know: Herndon and Dryhurst, visual artists and musicians, call this “spawning.” Like fish scattering eggs, artists train models on their entire body of work – then let AI generate endless new material in their style.

“Sampling dealt in citation. Spawning touches the DNA”, noted the designer Frank Chimero. “ This distinction matters because spawning raises the stakes in ways that sampling never did. When your work trains a model, what’s taken isn’t a note or a beat, but the sensibility and perspective of your practice.”

In other words, we’ve moved past Walter Benjamin’s seminal The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. We’re in the age of mechanical spawning: the machine doesn’t just replicate the work – it replicates the artist’s DNA.

On Top of That, Spotify is Making it Worse by Design

What is Spotify doing to prevent its catalog from being diluted? Here’s the issue: it isn’t. In fact, the company is flirting with the trend.

So far, I wrote that Spotify’s core metrics and product choices rewarded throughput over attention. An oversupply of cheap and AI-spawned content exploits those incentives. I concede that this behaviour is not unique to Spotify. Other leading streaming platforms are following a similar pattern.

But when it comes to AI-content, no company is more hypocrital. While Spotify claims to have removed 75+ million of “spammy” tracks, countless AI acts like “Midtown Players” and “The Tate Jackson Trio” appear as verified artists on the platform.

Will the 807,723 monthly listeners of the Tate Jackson Trio realize this band is completely fake? Spotify even granted it a verified badge. According to Artist.Tools Bot Checker, they could be earning up to $11,982 per month.

On Sept 25th, Spotify announced stricter rules against AI-slop content. But, in the same announcement, it stated that will still treat music “equally, regardless of the tools used to make it.” Translation: the feed will keep feeding.

Why won’t Spotify fix this? Follow the money: AI-generated music offers infinite supply at near-zero cost.

A notorious cartoon by Tom Toro, originally published in The New Yorker in 2012 (Source: CartoonStock.com)

But Spotify Has Been Undermining Artists for Years Anyway

Why is it so hard to trust Spotify’s promise to “champion stronger AI protections”? Hold my beer:

Fair compensation has never been Spotify’s priority. We all know how Spotify exploits artists best efforts, without giving anything back in return. There are so many people who wrote extensively about this, so I’ll cut short on this one. Let me just remind what Jim Anderson, a former Spotify executive credited with architecting the platform's system architecture, said during a 2019 interview at the SyncSummit New York conference. A musician was asking about the company’s financial model, and she replied: “The problem was to distribute music. Not to give you money, okay?”

She argued that the platform was originally created to solve the problems of music piracy and inefficient distribution, not to serve as a primary source of income for artists. Let them eat cake.Lower royalties for artists who want to be promoted: in late 2020, Spotify introduced a program called Discovery Mode, which imposes artists and labels a 30% royalty rates reduction in exchange for algorithmic promotion. Let them have smaller slices of an already tiny cake.

Even fewer royalties to real artists, thanks to ghost tracks: you may not be familiar with a program called Perfect Fit Content (PFC). It was introduced to Spotify editors in 2017 and we know its key details thanks to reporting by Swedish newspaper Dagens Nyheter and Liz Pelly, who has been digging into this for years in Harper’s Magazine.

PFC tracks are cheap tracks, made by anonymous musicians that Spotify puts into playlists for listeners who “wouldn’t know the difference”. They are typically bland, instrumental tracks, designed for background listening. They cost less to host because their creators often surrender certain royalty rights.

Some of Spotify’s most popular playlists, including those titled Ambient Relaxation, Deep Focus, and Bossa Nova Dinner, are almost entirely made up of PFC music. Pelly reports that “Spotify managers defended PFC to staff by claiming that the tracks were being used only for background music, so listeners wouldn’t know the difference, and that there was a low supply of music for these types of playlists anyway”.

“The problem was to distribute music. Not to give you money, okay?” ”

To secure an abundant supply of cheap content, Spotify partnered with a network of production companies devoted to this formula. A 2022 investigation by Dagens Nyheter found that just twenty songwriters were behind over 500 fake artists, with tracks appearing on major Spotify playlists. These songs have been played millions of time. The founder of one of those labels, Firefly Entertainment, reportedly had a long personal relationship with Nick Holmstén, a former global head of music at Spotify.

In the end, PFC comes down to this: why pay royalties to real artists when your platform is increasingly designed for lean-back listening?

According to Pelly, “Editors were soon encouraged by higher-ups, with increasing persistence, to add PFC songs to certain playlists”, and the suggestions became more aggressive over time. “Though Spotify denies that it is trying to increase PFC’s streamshare, internal Slack messages show members of the StraP team analyzing quarter-by-quarter growth and discussing how to increase the number of PFC stream”.

If you want a deeper perspective on these matters, Pelly’s new book, Mood Machine, is a must read.

Enough for now. I’ll just stick to my point one more time: why are we holding Spotify accountable for a questionable investment that the CEO did of his own money, and we are not complaining about deliberate company strategies that have massive cultural consequences?

3. Fixes & Future: Designing for Meaning

As surprisingly as it gets, I have good news – if you’re not a creator, though.

What Spotify Can Do To Fix This

So, Spotify didn’t break music alone – but its incentives are eroding how music’s value is formed. The fix isn’t posture or protest; it’s product design.

What does a platform for people who care about music look like?

Imagine a streaming product whose north star is attention, not mere plays. A few starting point:

Change the north star. Reward intentional listening and returning to the same song, artist, or album. Make these metrics visible to artists and users.

Rewire recommendations. Default algorithms to opt-in discovery modes for people seeking exploration; throttle autoplay for people who mostly save and replay.

Surface provenance. Show how a track was made (collaborators, samples, AI assistance) when it adds listener value, not as a compliance checkbox.

Elevate human curation. Let trusted curators compete with algorithms and publish their criteria. It’s worth the effort, even if scaling human expertise at that level is quite hard in practice: https://engineering.atspotify.com/2024/10/how-we-generated-millions-of-content-annotations

Tighten supply. Keep the anti-spam crusade going – kill mass-upload abusers, artificially short tracks, content mismatch, and impersonators swiftly.

But a braver change would be the one suggested by Amelia Fletcher, Professor of Competition Policy at the University of East Anglia. She wrote an open letter to Spotify CEO, arguing that the streaming giant should adopt a “user-centric model”, an alternative to the current model where money from listeners goes into a giant pool which is then paid out to artists based on their share of total streams across the whole platform.

In a user-centric model, “each subscriber’s payment would be shared proportionally between the tracks that individual listens to,” explains Fletcher. “So if you have someone who’s really enthusiastic about indie music, that money would get shared out among the artists that they listen to. More would be allocated per track if they listen carefully to fewer tracks than if they just have music playing all the time in the background.”

“If Spotify were serious about wanting to ‘reward real artists with real fanbases’, it could simply adopt a user-centric payment system.”

Fletcher, who is also musician, songwriter and co-fonder of an independent label, argues a user-centric model “would address the fraud issue more effectively. Because if one user is listening to loads of tracks for money, the proportion going to each track would go down.”

Rival streaming services Deezer and Soundcloud have both experimented with this model in partnerships with major labels. To be fair, Deezer’s model is more of a capped ‘pro-rata’ system, by which each individual’s streaming behavior can only bear a limited impact on Deezer’s pro-rata-based royalty payouts.

SoundCloud was way braver: they have successfully launched a "Fan-Powered Royalties" system, that operates on a pure user-centric principle, distributing a subscriber’s payment only to the artists they stream.

Two years have passed since Fletcher’s open letter. Some companies proved that a change is possible. Will Spotify CEO ever answer?

After the Flood: Why Abundance Will Spark a New Hunger for Meaning

I recently quoted Walter Benjamin’s classic essay The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (if you’re not familiar with it, Rebecca Marks offers a great perspective on how his ideas apply to AI).

TL;DR: Benjamin argued that mechanization stripped art of its “aura” – its unique presence and power. For him, the magic wasn’t just in the finished piece, but in the process of creation itself.

Ironically, his point feels both right and wrong today.

“Without real skills, the model’s limits become your own. You’re not producing, you’re just consuming.”

With AI-driven tools that automate the making and distribution of content, we’re drowning in art that’s been reduced to “content.” Yet these tools also resist the artist’s need for precision. They start simple and conversational, but quickly demand deep skill and specificity.

Pro users know this all too well. Craig Elimeliah, Chief Creative Officer at Code and Theory, one of the leading digital-first creative agencies, explained it perfectly:

“I want to have the ultimate level of control, so that there is differentiation in my craft – otherwise we're gonna drown ourselves in mediocrity. The tools might start off with being conversational but once you get in, they actually become really hard and precise. With tools like Runway or LTX the conversation actually is just the tip of the iceberg. Once you get an asset to work with, it gets hard. The average person wouldn't even know where to start. They don't even have the language to tell the system what to do after that point”.

He was talking about video production, but the same applies to music. If you’ve tried Suno, Udio or highly customizable platforms like Soundraw, you know the struggle: getting what’s in your head out of those tools is tough. Much of your effort gets lost behind algorithmic walls.

It feels like you’re creating something new – but without real skills, the model’s limits become your own. You’re not producing, you’re just consuming. And you will be forgotten soon enough.

“In a world of content abundance and zero-cost content creation, ‘meaning’ will command a premium”

That’s what Scott Belsky (co-founder of Behance, former CPO at Adobe) keeps reminding us: “In a world of content abundance and zero-cost content creation, ‘meaning’ will command a premium. (…) When anything becomes commoditized or ubiquitous – whether it is shoes or a popular restaurant that becomes a chain – consumers tend to crave a more scarce and differentiated version in response. What makes something scarce and differentiated? Meaning.”

In an unexpected twist, AI won’t kill music. But it might rewrite the rules of entertainment. For a decade, the creator economy thrived on low-effort content and free distribution via social media – two things AI does exceptionally well.

The real challenge now? Designing systems that can rescue what’s meaningful from this flood of music.

We May Be Overreacting, After All

Data already shows that the dream of “democratization” hit a hard limit: human attention. On streaming platforms, 87% of tracks never reach 1,000 streams – the minimum Spotify requires for payouts. The flood is real, but most of us don’t notice it.

AI-generated music performs even worse. Listeners aren’t flocking to it; they’re being served it by algorithms, and most don’t stick around.

Spotify doesn’t disclose data about the consumption of AI content, but Deezer did: even if 18% of songs uploaded daily are fully AI-generated (and Deezer now labels them), they account for just 0.5% of total streams. And here’s the kicker: up to 70% of those streams are fraudulent. In short, a lot of this content is junk, and much of the activity around it is spam.

Those frauds take many forms. The latest trend? Uploading AI-generated tracks to the pages of inactive bands or dead artists. Some profiles are literally vandalized.

But even fraudster can’t make people care. Strip out the fake streams, and these tracks barely exist.

“Up to 70% of streams of AI-generated music on Deezer are fraudulent: fraudsters use bots to listen to AI music and take the royalties”

It turns out nobody wants plastic food when they’re hungry. And nobody wants plastic music when they’re craving a real experience. The real battle isn’t about proving that human-made art is “better” or quoting Nick Cave’s famous line that “data doesn’t suffer.” That argument – that songs born from struggle are superior – feels like the same tired logic used against e-bikes: somehow, earning something through suffering makes us feel superior to those who didn’t.

Listeners don’t need Walter Benjamin to tell them AI music isn’t worth their time. The test isn’t how the song was made; it’s whether the experience moves them. It’s not about fairness or ethics – it’s about taste. A pizza made of plastic isn’t wrong because it’s fake; it’s wrong because the experience itself feels awful.

Life in plastic? Still not fantastic.